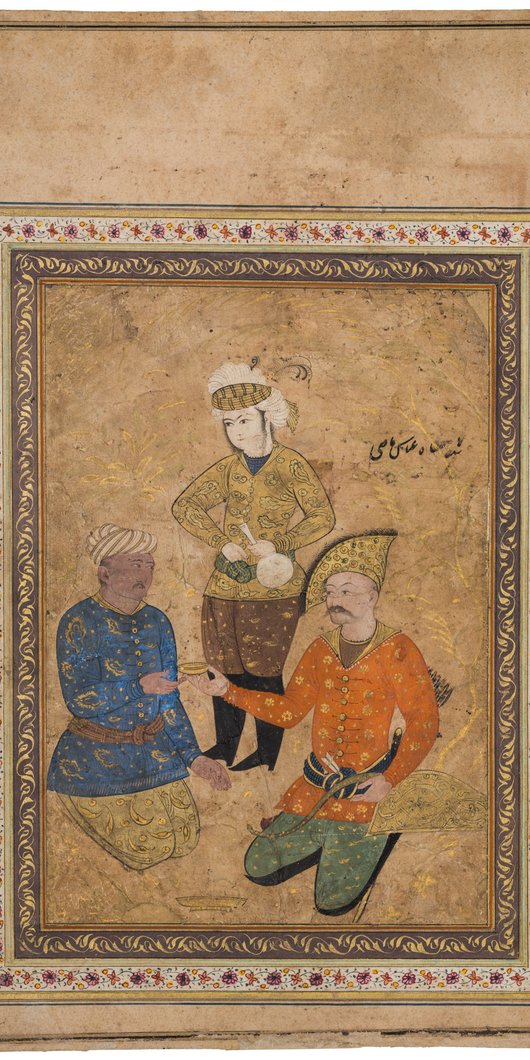

Isfahan’s thriving atmosphere was created by its cosmopolitan, multilingual and very diverse population. During the time of Shah ‘Abbas, Isfahan was home to a variety of religious communities and ethnic groups, including Armenians, Georgians and South Asians. The Armenians played a particularly significant role in state administration and commerce. To capitalise on their international trade network, Shah ‘Abbas forcibly relocated them from Julfa (modern-day Azerbaijan) to the newly founded quarter of New Julfa, in Isfahan. Many other people passed through the city, including travellers, merchants, missionaries and diplomats from all over Europe and India.

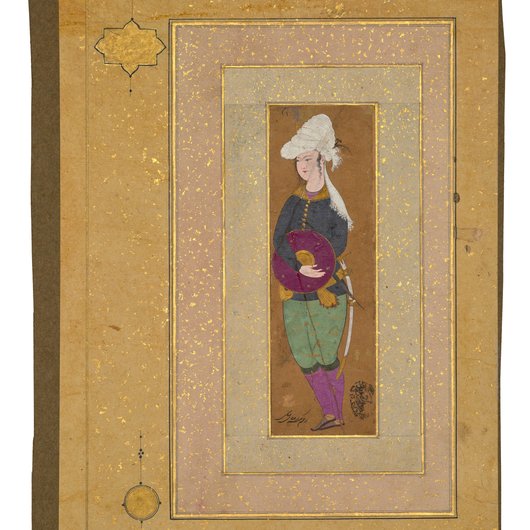

The richly brocaded silk garments worn in the painting of the lady shown above suggest she was a noblewoman, and her headdress identifies her as Armenian, possibly from the urban elite of Isfahan. Other notable aspects of her attire are her sleeveless jacket with fur-collar, striped brocade trousers, green high-heeled slippers and jewels.

Isfahan Fashion Guide

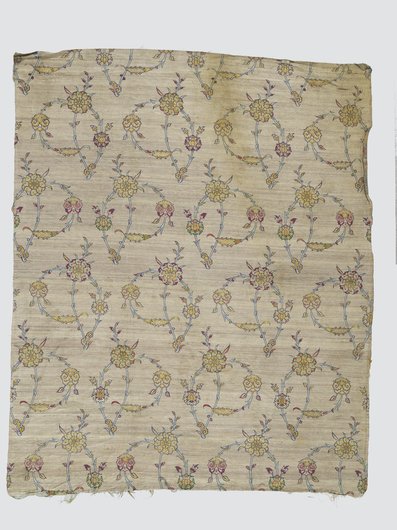

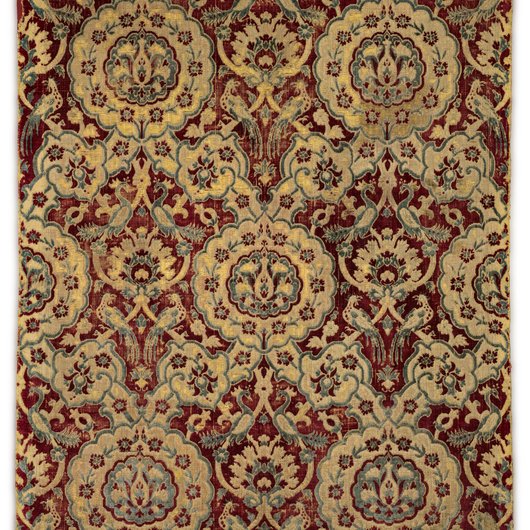

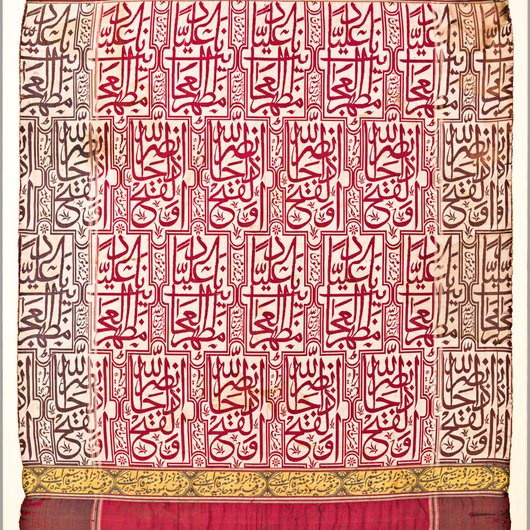

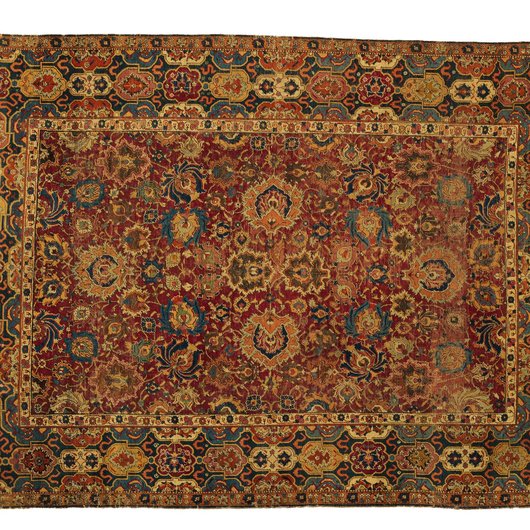

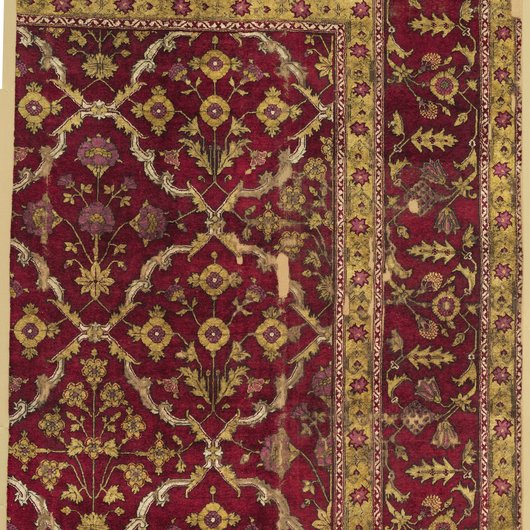

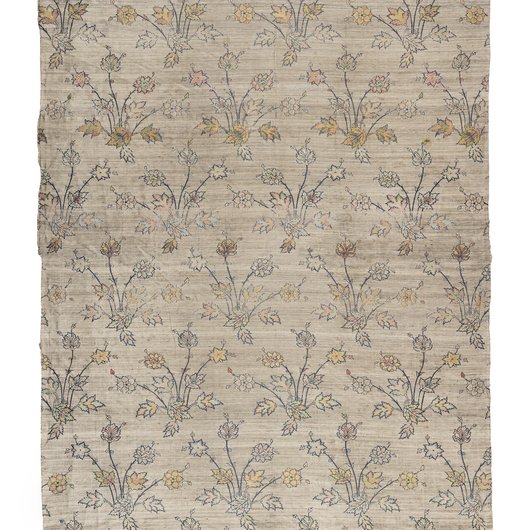

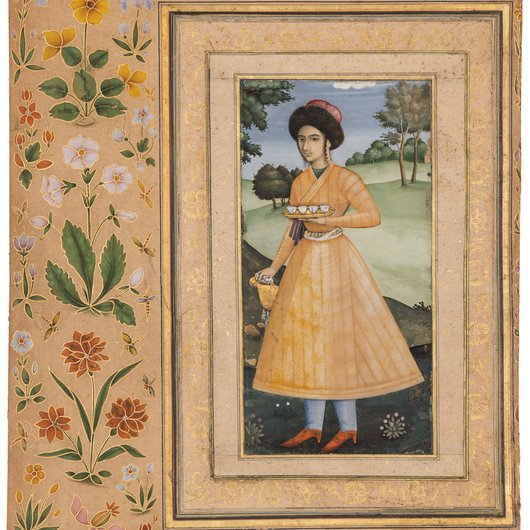

If silk formed the backbone of the Safavid economy, fashion was an essential aspect of the Safavid social scene, expressing status and identity, especially in a complex world comprising of people of diverse backgrounds and ethnicities. The historic textiles on display in the exhibition, along with court paintings showing these textiles being worn, give us a view of the highest, luxury end of fashion in Shah ‘Abbas’ time. This picture is rounded out by European engravings and travel accounts that offer a survey of other strata of Safavid society, particularly in cosmopolitan Isfahan. From these diverse sources we learn that the Safavid aesthetic favoured the layering of luxurious fabrics with contrasting patterns. Robes and overcoats were loose and flowing in the 16th century CE but were more fitted, in emulation of European styles, a century later.